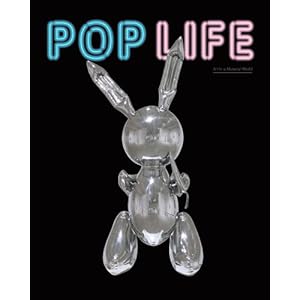

On 11 June 2010, Ottawa’s National Gallery opened their new special exhibit called Pop Life. The exhibit originally comes from the Tate Modern and before it opened at the National Gallery, a lot of people said that parts of the exhibit were quite controversial. I had heard before going that certain galleries would be for guests “18 and over” because of some sexual themes, but really just assumed that the so-called controversial aspects of the exhibit were exaggerated, as many things these days tend to be. In the weeks leading up to the opening of Pop Life, the Ottawa Citizen published a series of articles on the exhibit, including one about whether the exhibit was appropriate for children. Well, this just made me even more curious about the exhibit, as I’m certain it did many other potential museum-goers. So this past Thursday I decided I’d check out the exhibit and see what it was really all about.

On the whole, I really enjoyed the entire exhibit. It began with Andy

Warhol’s later work, a lot of which was perceived by the art community as him selling out. I also realized how creepy some of his works are, especially his self-portraits with his wild hair sticking up and relentless stare. Another notable area of the exhibit was the stunning recreation of Keith Haring’s Pop Shop. The actual Pop Shop was opened in 1986 in New York City, and the walls, floor, and ceiling were covered in black and white graffiti, with catchy music blasting through the room. In the Pop Shop, Haring sold t-shirts, buttons, and other pieces with his art on it, and what was really cool about Pop Life was that inside the recreated Pop Shop was a counter where the public could buy recreations of Haring’s original t-shirts and other things he sold in it. I think my favorite exhibit was by Damien Hirst, called Beautiful Inside My Head Forever which featured a lot of flashy pieces, like crystals strung together in a golden display case. There were also a lot of polka dots in his exhibit, and I do enjoy polka dots.

Warhol’s later work, a lot of which was perceived by the art community as him selling out. I also realized how creepy some of his works are, especially his self-portraits with his wild hair sticking up and relentless stare. Another notable area of the exhibit was the stunning recreation of Keith Haring’s Pop Shop. The actual Pop Shop was opened in 1986 in New York City, and the walls, floor, and ceiling were covered in black and white graffiti, with catchy music blasting through the room. In the Pop Shop, Haring sold t-shirts, buttons, and other pieces with his art on it, and what was really cool about Pop Life was that inside the recreated Pop Shop was a counter where the public could buy recreations of Haring’s original t-shirts and other things he sold in it. I think my favorite exhibit was by Damien Hirst, called Beautiful Inside My Head Forever which featured a lot of flashy pieces, like crystals strung together in a golden display case. There were also a lot of polka dots in his exhibit, and I do enjoy polka dots.

That was all fine and good, and then I got to the juicier parts of the exhibit. Most of it was thoroughly enjoyable, especially Takashi Murakami’s gallery. His was Japanese pop art and included a small “18 and over” area that had some gigantic statues in it (they looked like oversized children’s figurines) that were really fun. The one that made me laugh out loud is called My Lonesome Cowboy; racy, and hilariously so. On the whole, galleries like this (of which there are a couple), I could really appreciate and enjoy, but there was one gallery that seemed sorely out of place to me.

Before I begin my main criticism, I have to start off by saying I’m obviously untrained in art appreciation, and I only make my own assumptions when I see it. However, it was the Jeff Koons Made in Heaven gallery that really made me think about what art is and what should be in a museum. It was cordoned off by a “18 and over” sign and guarded by a security guard, so I knew it would be explicit, to say the least. I walked into the gallery and was confronted by full-on pornography. Graphic pornography that I’m still confused as to how it even falls into the pop art category. Although there were a couple of non-pornographic pieces in the room (like a really beautiful glass flowers creation) that I could see the value of, the graphic pictures on the walls were very extreme. The story is this: the artist, Koons, saw porn star Ilone Staller (a.k.a. La Cicciolina) in a porn magazine, she became his muse, they ended up getting married, and he shot all sorts of pictures of them engaging in certain activities. Which is fine and dandy, but it seemed to have no relation to pop art other than association with the artist, and these works are certainly not your typical pop art.

Before I begin my main criticism, I have to start off by saying I’m obviously untrained in art appreciation, and I only make my own assumptions when I see it. However, it was the Jeff Koons Made in Heaven gallery that really made me think about what art is and what should be in a museum. It was cordoned off by a “18 and over” sign and guarded by a security guard, so I knew it would be explicit, to say the least. I walked into the gallery and was confronted by full-on pornography. Graphic pornography that I’m still confused as to how it even falls into the pop art category. Although there were a couple of non-pornographic pieces in the room (like a really beautiful glass flowers creation) that I could see the value of, the graphic pictures on the walls were very extreme. The story is this: the artist, Koons, saw porn star Ilone Staller (a.k.a. La Cicciolina) in a porn magazine, she became his muse, they ended up getting married, and he shot all sorts of pictures of them engaging in certain activities. Which is fine and dandy, but it seemed to have no relation to pop art other than association with the artist, and these works are certainly not your typical pop art.

Here is where my real problem with this area of the exhibit is: to me, this so-called art looks like something anyone could pick up and find in a dirty magazine. I saw no artistic merit to it and there was really nothing special about it. So if this type of porn finds itself in the National Gallery, what makes it so different from other porn? Why not just put all porn on display in the museum? I’m not trying to say that porn is not art, because maybe it is, to some people. But if this porn is art, then all porn is art, and all porn should also be in this museum’s exhibit. This section of the exhibit did not belong and seemed very out of place. Maybe if the exhibit was all about pornography or the history of pornography it would be better suited, but this was just awkward and seemed very random. Also, I think with the other “18 and over” galleries, I wouldn’t have a problem allowing children in (with over-18 supervision, of course!), but this gallery was just a little much in terms of intensity.

Final thoughts on Pop Life: awesome exhibit and loved nearly all of it. Not trying to rain on anyone’s parade by complaining about this porn debacle, but really, pay attention to the exhibit’s goals and determine if it really fits within that definition.